Greeting, Professor Faulken - My Experiences with Wargames.

Sunday, October 16, 2011 at 11:49PM

Sunday, October 16, 2011 at 11:49PM

As I've mentioned before in my reviews and editorials, I tend to be a regular fixture at thrift stores. Throughout the years I have found and collected a small pile of unpunched wargames. These have remained unpunched all of these years despite a definite curiosity on my part to learn what has driven such a passionate segment of the gaming hobby for so many decades. However, whenever I open up one of these large-scale games, and entertain the idea of playing one, I get roughly one third of the way through the rulebook before my brain begins to shut down.

I'm not exactly sure why this happens; I enjoy many complex games, and usually have no problem embracing new rulesets. Perhaps it is because wargames have a storied history, and just like eurogames have a vocabulary of mechanics that are intrinsically understood by the players of that genre. Where Euros have understood mechanics such as worker placement and hidden role selection, wargames also have their own set of mechanics and ideas; concepts like: zone of control, stacking, and supply lines. Without really understanding how these these mechanics worked and interacted with each other, I had a hard time visualizing how the game would play out, especially when confronting them all at the same time, and I found myself a bit intimidated.

Recently, I decided to take the plunge, and really learn what wargaming is all about. Alan Emrich of Victory Point Games was very gracious to facilitate this process by selecting a few games for me that he thought a beginner should start out with. I hope to chronicle my exploration of wargaming through a series of game reviews of these titles. My reviews will be from the viewpoint of a total wargame beginner, so may not have the depth of experience found in a similar review from a hardened grognard, but since these games are meant to serve as an introduction to the genre, I hope that my experiences will resonate with others in my position.

I am also bringing along for the ride, my 15 year old daughter - who, at first, was abject with the thought of having to play with armies and tanks. She is definitely not a stranger to complex strategy games, and can mow through heavy hitting euros like Dominant Species. But, she is new to wargames, and has the unique perspective of someone who really doesn't think that she will find anything interesting in the genre. Although, I was very surprised at the direction her opinion turned when we began to play these games.

As of this writing I have played a few of the games, and I am really starting to understand why people enjoy this genre of games. I consider myself to be very open minded, and try very hard not to generate any preconceived bias in my thought process, but I was surprised at how much I really misunderstood about wargames. I lived my childhood as a boy growing up in the 80's, and as a result, my view of games was strongly molded by the “Ameritrash” games of that era. Often military in nature, and usually requiring a handful of dice, the typical "Ameritrash" didn't have a whole lot of deep strategy in it, instead focusing on a more narrative, luck based experience. I had assumed that because wargames consisted of dice, and strive to simulate the events that occurred during historic battles, that they would share this “dicefest” type of randomness. I was very wrong in this assumption, and wonder how many others like me may share this misconception.

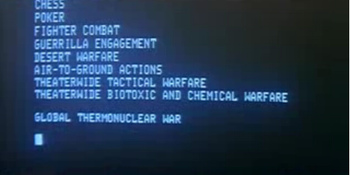

What I discovered was that the dice in the hex and counter type wargames that I played did not generate a random experience, but instead were used to add a very limited about of randomness to the game - more of a vehicle to simulate calculated risk. This risk, and uncertainty played a huge part in driving strategic decisions. Like the WOPR computer from the movie Wargames surmised when playing simulations of Global Thermonuclear War, “The only winning move is not to play”; it is often strategically critical to hold off on even making an attack roll unless you are assured that any number to come up on the die will either further your strategy, or at worst, result in a draw. This completely changed my understanding of how dice could be used to simulate randomness in games - in a limited, controlled manner that did not detract from the strategy of the games.

Over the next few weeks I will post my reviews and musings about the games I have played, starting with the 2007 Victory Point Games reprint of the 1975 tutorial game Strike Force One.

Jump to an article in the series:

Board Games,

Board Games,  Victory Point Games,

Victory Point Games,  reviews,

reviews,  wargames in

wargames in  Board Games

Board Games