Hot on the heels of the debut release of Nightfall, game designer David Gregg and publisher Alderac Entertainment Group are unleashing the shadowy creatures of Nightfall: Martial Law into the sticky summer nights of Atlanta, Georgia. With a new setting, and a new cast of characters, Nightfall: Martial Law serves as both an expansion to the original Nightfall game and a standalone introduction to the series. Martial Law also ups the ante a bit by introducing a new game mechanic called “feeding” to the game, as well as a new wound card Ability.

In the Nightfall universe, the world has mysteriously fallen into perpetual darkness, with humankind and the supernatural locked in a deadly battle, vying for the future of Earth. You are secretly controlling these Ghouls, Vampires, Werewolves, and Humans to the benefit of your own nefarious agenda, and unleashing their rage upon your opponents. Players bring cards representing creatures and actions onto the table through an innovative process called “chaining”, where cards can be played off of one another by matching colored icons. Since I have already discussed the rules and theme of Nightfall in my review of the original game, this review will focus on the changes that Nightfall: Martial Law brings to the series.

The Game:

The first thing that is apparent when looking at Nightfall: Martial Law is that its box is the same size, and shares the same build quality and card organization system as the original Nightfall box. With so much space in the original box meant for expansions, it may seem confusing that Nightfall: Martial Law doesn’t come in a smaller box. But, Martial Law is more than just an expansion for the original; it is also a standalone game that contains the starter decks and wound cards included with the previous release. With a limited production pi peline, AEG had anticipated that the first printing of Nightfall could sell out before Martial Law was released, potentially alienating new customers who would be unable to find the original game. By including all of the components in Martial Law, AEG is ensuring that players can jump straight into the world of Nightfall, even if they cannot find the base game on their retailer's shelf.

peline, AEG had anticipated that the first printing of Nightfall could sell out before Martial Law was released, potentially alienating new customers who would be unable to find the original game. By including all of the components in Martial Law, AEG is ensuring that players can jump straight into the world of Nightfall, even if they cannot find the base game on their retailer's shelf.

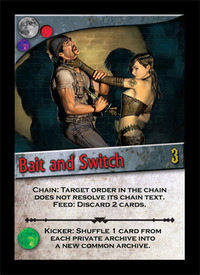

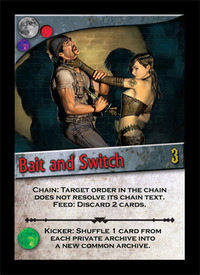

Like Nightfall, the cards in Martial Law are beautifully illustrated, and capture the vivid, gritty art style found in many high quality graphic novels. I really enjoy the dark, urban style feel of the artwork, and find that it is very effective at communicating the theme of the game. I do, however, have one minor gripe with the cards in Martial Law. The order and draft cards don’t have any icons on them to differentiate them from those in the original Nightfall set. This made cleanup slightly more difficult after playing a game that mixed cards from both sets. However, the card dividers indicate the set that they are from, so I found that it was easiest to look for the empty spaces in the box, and then grab the correct pile from the table. Odds are, if you are mixing cards from the two sets, that you will be keeping all of the cards in the same box anyway, so the issue becomes moot.

A second issue I ran across with the draft cards in Martial Law was a printing error in the kicker text. The spacing between lines was incorrect on some of the cards, causing portions of text to overlap, contain misaligned letters, or exhibit strange blob-like artifacts. I do not know if it is a widespread issue, or is isolated to my copy, but the cards were still readable, and the issue only manifested on the draft cards.

When looking through the cards, I was pleasantly surprised at the variety and relative number of the various types of minions. While the card selection in Nightfall was mostly dominated by vampires, Martial Law mixes things up a bit by increasing the number of humans and werewolves. Even though there is more of a variety in the creature cards, the vampires still have the advantage of numbers - although this advantage is mitigated a bit by some new action cards that specifically target the bloodsuckers. ("Silver Stake - Chain: Destroy target Vampire. Destroy Target Lycanthrope." and "Shining Cross - Chain: Inflict damage on each player equal to the number of vampires they have in play.")

When looking through the cards, I was pleasantly surprised at the variety and relative number of the various types of minions. While the card selection in Nightfall was mostly dominated by vampires, Martial Law mixes things up a bit by increasing the number of humans and werewolves. Even though there is more of a variety in the creature cards, the vampires still have the advantage of numbers - although this advantage is mitigated a bit by some new action cards that specifically target the bloodsuckers. ("Silver Stake - Chain: Destroy target Vampire. Destroy Target Lycanthrope." and "Shining Cross - Chain: Inflict damage on each player equal to the number of vampires they have in play.")

Martial Law ships with a revised version of the Nightfall manual which adds some new rules, as well as some new fiction surrounding the characters found in the game. The biggest addition is a new mechanic called “Feeding”. Feeding allows a player to repeat certain effects multiple times by discarding cards from his hand. Each card that is discarded causes the effect to repeat once, and a player with a handfull of cards could produce potentially devastating results. Feed effects can be found in both chain and kicker portions of the cards, opening up the possibility for some extremely brutal combinations.

Along with the wound cards found in Nightfall, Martial Law contains a deck of cards with a new wound effect that allows players to increase the strength of their minions. These new wound cards also take advantage of the feed effect, allowing players to discard multiple wounds to buff up their creatures. The inclusion of multiple wound effects adds a new layer of decision making. While the original wound effect fills the player’s hand with cards, and gives him an advantage when purchasing cards or creating combos, the new wound cards allow him to convert his wounds into raw power for his minions – if they can survive until his next turn.

Although the cards in Martial Law work great together, and form a solid gameplay experience on their own, I love throwing the cards from both sets together and drafting from a huge pool of options. With the larger numbe r of cards to pick from, Martial Law includes some new drafting rules for mixing the game sets. Instead of the usual four card packets, five card packets are used. These cards are drafted normally, with the exception of the last remaining card, which is discarded. The addition of that single card to each packet makes a big difference in the perceived selection available when drafting, and makes the drafting portion of the game much more enjoyable.

r of cards to pick from, Martial Law includes some new drafting rules for mixing the game sets. Instead of the usual four card packets, five card packets are used. These cards are drafted normally, with the exception of the last remaining card, which is discarded. The addition of that single card to each packet makes a big difference in the perceived selection available when drafting, and makes the drafting portion of the game much more enjoyable.

Conclusion:

Martial Law easily stands on its own. Even with the different selection of cards, it gives a satisfying experience on par with Nightfall, and the variety of cards and the story driven connections between the cards may even make it more compelling from a thematic standpoint. The cards in Martial Law are also more varied and interesting in their effects, but often much more brutal than vanilla Nightfall. The brutality can turn even more vicious when pumping pain into opponents through the unyielding feed mechanic. I can imagine that this would make Martial Law a bit more daunting for the new player, and Nightfall may serve as a better introductory experience.

For the experienced player, however, Martial Law invigorates the game by speeding up the pace, adding more complex card effects, and increasing the "take that" factor. Cards like "Hysteria - Chain: Target minion inflicts damage on itself and its controller equal to its strength. Kicker: Inflict 2 damage on target player" can be devastating to a player who isn't prepared. But the higher stakes of the new cards really force players to think critically about the cards they draft and play, and that really increases the fun factor.

If you didn't like the conflict in Nightfall, then Martial Law is not going to make a convert out of you. But, if you can't get enough of the brutal head-to-head confrontation of the original, then you are in for a definate treat. I look forward to many enjoyable hours of exploring the different stategies and card interactions within Martial Law and Nightfall, and can't wait to bring it back to the table.

Nerdbloggers.com was supplied with a copy of this game by its publisher for the purpose of writing this review. The content of this review was not influenced by advertisers or an affiliate partnership, nor was it written for the sole purpose of promoting a product.

Thursday, September 8, 2011 at 01:07AM

Thursday, September 8, 2011 at 01:07AM

complexity by introducing pick up and deliver, area control, and set collection mechanics to the formula.

complexity by introducing pick up and deliver, area control, and set collection mechanics to the formula. Board Games,

Board Games,  PARSEC,

PARSEC,  Sean Young,

Sean Young,  Victory Point Games,

Victory Point Games,  review in

review in  Board Games

Board Games