Preview: Visitor in Blackwood Grove

Friday, August 11, 2017 at 01:58PM

Friday, August 11, 2017 at 01:58PM (Note: Like all Nerdbloggers Kickstarter or early-access previews, we received no compensation for this preview. In the case of Visitor in Blackwood Grove, my preview is based on an early prototype that was desktop printed. The images in the preview are from a later revision, but still not finalized assets.)

The site has been on a long break recently as our personal lives and careers have limited the time that we can spend on nerdy stuff (and I think all of us have opted to play games, read books and comics, and keep up with movies with the time we have rather than write about those things). Things are getting a bit more settled, for me at least, and I’ve got a ton of content in various stages of completion rolling out soon. To start that off, here is a quick look at a new deductive/inductive logic game from Tiltfactor and designers Mary Flanagan and Max Seidman : VISITOR in Blackwood Grove.

The site has been on a long break recently as our personal lives and careers have limited the time that we can spend on nerdy stuff (and I think all of us have opted to play games, read books and comics, and keep up with movies with the time we have rather than write about those things). Things are getting a bit more settled, for me at least, and I’ve got a ton of content in various stages of completion rolling out soon. To start that off, here is a quick look at a new deductive/inductive logic game from Tiltfactor and designers Mary Flanagan and Max Seidman : VISITOR in Blackwood Grove.

The Pitch: An alien craft has crashed in the woods. Government agents arrive to dissect it at the same time a kid who has seen the crash arrives to investigate. A “shimmering semi-permeable” barrier surrounds the alien ship. The kid and the agent(s) will compete to figure out just what types of objects can penetrate the barrier. If an agent does so first, he or she wins. If the kid is successful, he or she joins the alien player in victory.

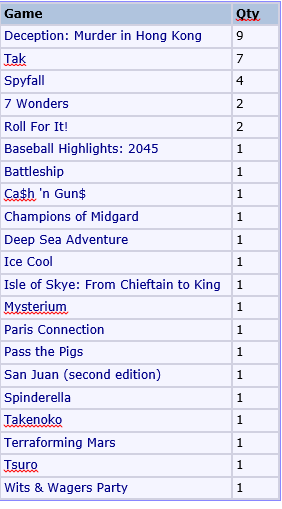

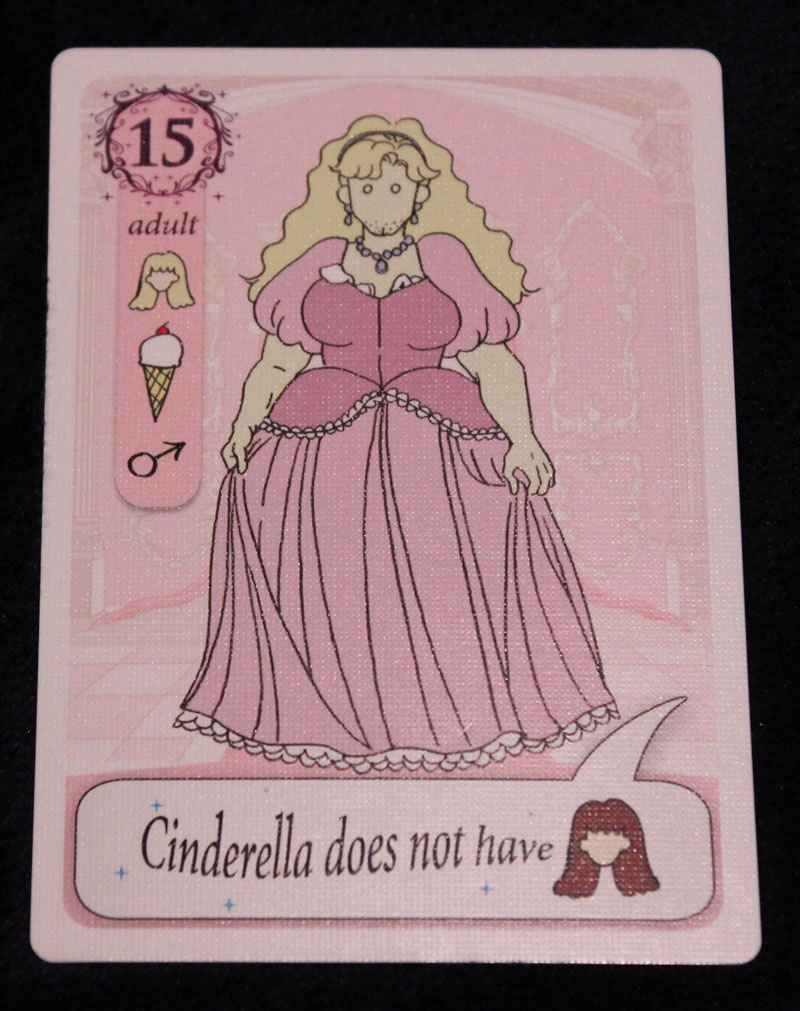

The Play: The game begins with the alien player secretly constructing a rule about what can get through the barrier. This could be something like (“things you can buy at Wal-mart” ) or (“Things that would fit in a backpack”). The alien then sorts two face up cards by placing them either inside or outside the barrier. One player plays the kid. Up to three other players can play agents. All players are dealt a hand of cards and take similar, but slightly asymmetrical turns. The agents (who are playing as individuals) slide a card to the alien on their turn. The alien then places the card either inside or outside the barrier, oriented in a way that only that agent can see it. The kid player up to three cards while predicting whether they would make it through the barrier or not. When the alien’s turn comes around, he places one of the cards in his hand face up based on the rule. Either player can instead try to guess the rule by correctly sorting four random cards from the deck (the agents can do this from the start; the kid has to build trust first by correctly predicting cards). If the agents or kid correctly sort the four cards before the alien plays his last card, the game ends with either an agent win or a kid plus alien win. If the alien plays his last card, the agents win.

Sample Play:

Let’s say as an alien, you flip over these two starting cards (a pennant and a cell phone):

You then look at your hand and the two cards and decide on a rule. For these two you might concoct something like “objects that often have buttons” or “things that you use to communicate.” Having done that, you would then sort the two cards, placing the one that passes the rule inside the barrier and the one that doesn’t outside the barrier (the rule could also be one that leaves both items outside or inside the barrier instead). Let’s say you chose “objects that usually have buttons” and sorted the phone in and the pennant out, for this example.

The agents turn would be next, and he would likely slide a card over to you for analysis. Maybe this one:

Since a car usually have buttons, you would place the card in a stand inside the barrier and orient it in a way only that agent could see.

After each agent has done the same, the kid player would then get a chance to predict. He does so openly at the start of the game, so the agents will get all of the information the kid does, though that will change as the trust between the alien and the kid goes up on a rewards track with each correct prediction.

This would continue with the alien placing new objects from his hand on the alien turn until one of the players is able to correctly sort four random cards or until the alien runs out of cards.

My Thoughts: I am a big fan of Zendo, a game from Looney Labs that has one player creating a rule about the way pyramid groups are composed and the other players trying to construct groups that match the rules in order to eventually guess the rule. Visitor in Blackwood Grove provides a similar experience in a very portable package. Games are short (ten minutes on average) and it works with everyone from young kids to adults. It is very non-gamer friendly. Given the reasonable price and broad range of gaming situations this game is good for, I have no problem recommending giving it a look and backing it if you like quick, light deduction games with flexibility to make become heavier and more thinky for groups that want that.

What I liked: Fast, easy to teach and understand, fun theme, just thinky enough to keep gamers attention but not cause non-gamers to zone out. This is a wonderful entry into the deductive/inductive logic game arena and one of the best I've played that could be called a family game.

What I didn’t like: the game is heavily reliant on the alien player coming up with a good rule, and unlike Zendo, the rule-making here is kind of wide open. I saw some analysis paralysis and some bad rules-- making the game a bit fragile for a family, non-gamer* setting (I think gamers will mostly do well from the start). This gripe is somewhat invalidated by the fact that someone can win without actually guessing the correct rule as long as they sort the cards correctly, but I still hope that the final production will includes a good list of suggestions that players could use while learning to create their own.

*Yes, I know, non-gamer is a dumb term to use to refer to people who aren’t deeply rooted in gaming as a hobby, but it seems to have worked its way into the gamer lexicon.

Note: If this game sounds good to you, go check out the Kickstarter. It is reasonably priced and has already made its publication goal, but there are a few stretch goals you can help them out with. With the current cost and contents, this is shaping up to be a real bargain.